Trench Foot From A Foxhole May Have Made The Difference For Alhambra Man To Survive Battle Of The Bulge

By Michael Lawrence

It was a miserable land full of dread and wet snow. This is what faced Alhambra resident Dr. Rod Ingraham in the days before Christmas of 1944. A member of the Army’s 99th division, he was stationed in what they believed was the “quiet zone:” the Ardennes forests of Belgium. Neither Ingraham, nor his fellow teenage troopers, had any idea that they would be playing a crucial part in stopping Hitler’s last gamble to reverse the Allied advance into Germany, the Battle of the Bulge – or that about half of them would perish.

Soldiers taking refuge in fox holes during the Battle of the Bulge | US Army

“Considering the life span of an infantryman on the front lines, if I had gotten there much sooner I would not be here to tell about it,” Ingraham recalls in memoirs he wrote for his grandchildren. “It is one of the tragedies of war that many of the most dedicated and self-sacrificing men are killed and society is denied the benefits of any later contributions that they might make.”

Sgt. Rod Ingraham in full battle gear

Ingraham’s regiment had arrived a month earlier in the front line positions near Krinkelt, Belgium. The 19-year-old from Anderson, California was charged with holding the lines against the Germans in a wooded area of fir and pine. He shared a snow-covered foxhole with another soldier that was seven feet by three feet and about two feet deep. It did not take long in this environment for Ingraham to develop trench foot, a common and painful condition. His affliction worsened and he was assigned duty at the regimental headquarters a mile behind the front lines. Ingraham said that his reassignment probably saved his life: A few days after he left the front lines, he said, “Half of my squad was killed by a machine gun burst.”

In the early hours of December 16th, 1944, the Germans unleashed one of the heaviest artillery bombardments of the war along an 80-mile front. Hitler’s surprise offensive was designed to drive a wedge into the American positions and capture the port city of Antwerp. Ingraham soon found himself in a foxhole on the Elsenborn Ridge directly in the path of the 12th Panzer division.

During the fighting on the Elsenborn Ridge, Ingraham describes life in a foxhole:

“We always had two men to a foxhole. At night one person stayed awake while the other slept. We usually had one hour on and one hour off. I had been on the front line a couple of days when I got a new partner. He was an Italian boy from Brooklyn, New York. He had just finished basic training and been shipped over. His first words were, ‘So this is lock and load?’ He could not believe that this was the front line of an ongoing war. Everything was quiet and people were walking around. I told him that in an hour or two we would be getting an artillery barrage. It was right on time. Give the Germans credit for being able to keep a schedule. A few landed fairly close, and I suddenly realized that he was hugging me.”

The assaults by waves of German soldiers on the Elsenborne Ridge was so intense that on several occasions the bodies of the German troops shot at point-blank range fell into the foxholes. The weather cleared on the 23rd and the skies were filled with American fighters and bombers that inflicted heavy losses on the German positions. The Germans continued the attack on the Elsenborn Ridge until the 26th of December and were stopped by massive fire from artillery.

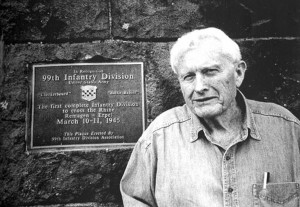

Dr. Ingraham in 2000 at the Remagen Ridge

Stubborn resistance by units like the 99th division on the Elsenborn Ridge denied vital roads and delayed the German attack resulting only in a large bulge in the Allied lines. The Battle of the Bulge, so named because of the westward bulging shape of the battleground on a map, lasted from mid-December 1944 to the end of January 1945.

The Allies began a counter offensive in early January and with the help of air power drove the Germans back forcing them to abandon most of their equipment. The losses the Germans suffered could not be replaced and as a result Hitler weakened his defensives on both the Eastern and Western fronts.

After the hard fighting in January, Ingraham served as a squad leader and led his 12 men on campaigns in the Monschau Forests, the crossing of the Remagen Bridge and the clearing of the Ruhr Pocket until the end of the war.

When the war was over, Ingraham returned to his native California, attending UC Davis. He then worked as a veterinarian in Coachella with the dairy industry, before receiving a doctorate in animal physiology from Iowa State, which he taught at Louisiana State University. After retiring, he returned to California, this time moving to Alhambra in 1997. Despite all of his accomplishments during the course of a long life the shadow of the Battle of the Bulge, 66 years ago this week, continues to loom large. “This period was only 3.5% of my life, yet as I grow older it seems to make up a disproportionate amount of time in my thought,” he said. “I would not like to have my life evaluated mainly on what I accomplished during that period. I was not a hero or an imaginative leader, but I take pride that I put my life on the line and did what I was asked to do.”

Submitted by Michael Lawrence