MANHATTAN PROJECT

EDITOR’S NOTE: We are republishing this article because the first page was not included in the October issue. It was lost in cyber space.

MY EXPERIENCES WORKING ON THE MANHATTAN PROJECT IN 1943 to 1946

By: Marijune Wissmann

A few weeks ago WGN Cable television featured a series about the Manhattan Project (atom bomb project) about the scientists who worked on the project during World War 2. In the summer of I943 while at the University of Chicago I was hired by the project as a steno.

At that time, the campus was a very exciting place; dormitories were filled with members of the armed forces, classes in Japanese, meteorology cadets, navy radio students, etc. The athletic field, Stagg Field was taken over by a secret project, guarded by pistol-packing soldiers as well as other secret locations on Chicago’s Southside.

The war news at that time was grim. Britain was being blitzed, France had fallen and so had Corregidor in the Pacific. I was interviewed for this secret project for over an hour, the army officer told me to be very truthful about my life as I would be examined by the FBI. When I signed the contract, the last clause on the page indicated that if I divulged any secrets in my work I would be guilty of violating the espionage act and it was punishable by death. I realized that I was involved in something sinister and it if was for the war effort it was worth it.

There were army recruits called SEDs or Special Engineering Division composed of soldiers plucked from army bases with degrees in physics, chemistry, biology and other science backgrounds. I was assigned to a typing pool to type secret reports made by famous scientists from all over the world, many of them Nobel winners. The foreign scientists wrote their reports in beautiful script while the Americans used the primitive dictaphones. There were many code words used to disguise elements and procedures.

We were lectured by the Anny MPs of the need to remain silent about our work. Our friends on campus were very curious about the project and we were comfortable in our own group Even the wives of the scientists pressed us for information about what their husbands were doing.

In 1944 I was promoted as a secretary to Dr. Samuel Schwartz, a section chief of the medical section. which carefully watched the blood levels and urine samples of the men working on the atomic pile in the guarded football field. The scientists were so busy our lab technicians had to stalk them to take their blood samples.

In the winter of 1943 many of the “long hairs” which we called the scientists began to disappear. No one knew where they had gone. Some of the wives and families also, had left Chicago. A friend of Laura Fermy received a post card saying she was on a high mountain in the southwest.

The wives did not stay very long in Los Alamos, New Mexico, the mountain city 40 miles northwest of Santa Fe. Just to travel the road to the high city was very frightening. The families lived in Quonset huts, cottages, and barracks, there was a water shortage, mail was censored and husbands worked long hours. General Groves was a difficult taskmaster and expected the SED detachment to stage military drills and behave militarily, when they had received very little training. Most of the young scientists worked long hours on complicated and secret assignments.

The general, in his uniform, was very splendid and impressive. His boots were highly polished, despite the muddy streets with no names and there were no sidewalks. We were in a mesa, about 7500 feet high, surrounded by high mountains, protected from winds, but summers were hot and winters had snow from time to time.

The staff in Chicago was shocked when President Franklin Roosevelt died in April 1945. There were rumors that Vice President, Harry Truman, would not fund the project and we would be without jobs. The Vice President was not aware of the existence of the project and it was the responsibility of the Secretary of State to convince him to continue the work and funding to build the bomb and end the war. We were relieved to learn that it was full speed ahead.

That summer we knew something big was going on at Los Alamos. The scientists gathered around the telephones for a few days, waiting for some mysterious message. When word came that a successful testing of the bomb at White Sands had been completed successfully there was a small celebration but we were told very little.

When the first bomb was dropped at Hiroshima we were shocked but relieved that the war would soon be over. In Chicago when the war was officially over, people went wild. They danced in the streets of the Loop, we made punch fortified with alcohol. It was party time.

After a few days of celebrating, the Trustees of the University of Chicago gave the project its walking papers. We were evicted. Knowing that this would come about, the government bought land in southwest Chicago and already the Argonne National Laboratory was under construction.

Many of the WACs were being discharged from Los Alamos at this time, leaving Dr. Teller with a shortage of stenos. Dr. Oppenheimer wanted to close the research but President Truman gave Dr. Teller the funding to continue the research on the hydrogen bomb.

There are many rumors about deaths due to radiation at Los Alamos, We were still working at Drexel House in Chicago when word that a young scientist had been injured in an accident. He had absorbed 880 roentgens of radiation by shielding other workers following spillage of radioactive material. He died a very painful death and the doctors who flew out from Chicago could not save him.

Several stenos from Chicago decided to take Dr. Teller’s offer to go to Los Alamos as the Chicago project was moving to Argonne. I had a boyfriend in Los Angeles so signed up and my friends left on the Super Chief to a little town called Lamy 20 miles from Santa Fe. A young corporal in a staff car met us, and up the mountain we went.

Army trucks came driving down the one lane road, boulders came plunging down the cliffs and we were terrified. We climbed to 8,000 feet and came down 1,000 feet to a mesa below. The mesa was called the Parajita Plateau. The city consisted of old CCC camps, Quonset huts, and a few homes. We were assigned to the former WAC barracks. There were showers, no bathtubs and a shortage of water. We ate our meals in the mess hall, and the food was good.

Our mail was censored, going in and out. When it rained we wore GI boots. Once a month we would go to Santa Fe enjoy a tub bath and go to a movie. We had no shortage of escorts, as there were very single girls and the SEDs and MPs were very attentive. Years later we learned that the bar tender at the La Fonda Hotel was actually an FBI man.

One weekend a group of us were having lunch at the Fred Harvey restaurant in Santa Fe and saw three very skeletal soldiers at the next table. They had been released from any army hospital in the Philippines where they had been taken after being released from a Japanese Prisoner of War camp. They were members of the 200th and 515th Coast Artillery Regiments formed from the New Mexico National Guard. At the beginning of the war General McArthur had them sent to the Philippines to train troops there to fight the Japanese. Of the 2,000 troops who were sent, only l,000 came back. The names of their fellow comrades are carved on a monument in Santa Fe.

There are many of the persons who participated in the construction of the atomic bomb who have guilt feelings but President Truman did not want another soldier to die when we did have the means to end the war.

In the National Archives in Washingnton DC hidden away for nearly four decades are the plans for the invasion of Japan now declassified called Operation Downfall. James Martin David has written a book called “An Invasion Not Found in History Books”.

In this book are the horrific details of the invasion, which would involve and island by island assault by American marines with losses as we suffered in Iwo Jima and other heavily fortified islands. Our navy would be attacked by waves of suicide planes. 500,000 American troops would be killed. The battle for Japan would be the biggest blood bath in the history of modern warfare.

As soon as discharge physicals and security lectures ceased, the professors and their families went back to their universities, the junior scientists enrolled in graduate schools, the workers at the University of Chicago all moved to jobs at the Argonne National Laboratory, a new research facility south west of Chicago. Many of my girl friends married the MPs and engineers; Irene Uhrich went to medical school and had a practice at Los Alamos, married Slim Boone, a former MP who became director of security.

Having a computer is such a help looking up old friends. Many of the scientists made great careers including Professor Glenn Seaborg, a native of Upper Michigan, whose Swedish parents moved to Los Angeles when he was ten. He won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1951 and gave his acceptance address in fluent Swedish, to the delight of the Swedish royalty.

Aage Bohr, the son of Niels Bohr was only 22 years old when he and his dad, Niels Bohr were flown to the United states from Sweden where the family had a close escape from the Germans who were trying to capture Niels for his knowledge of the atomic bomb. Aage, himself, received a Nobel Prize after he took over the Bohr Institute for Theoretical Physics.

Other scientists, including prankster, Richard Feynman, Dr. Louis Hempelman, and other professors came to Cal Tech.

I left Los Alamos in November of 1946 to elope to Las Vegas with Frank Wissmann, a law student at USC in Los Angeles, where we have lived ever since then.

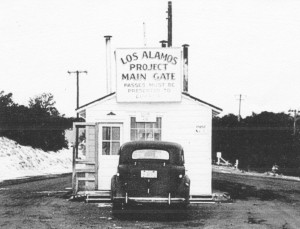

- Main gate at Los Alamos Project

- Glenn Theodore Seaborg

- Dr. Niels Bohr skiing on Sawyer Hill

- The Young Scientists

- Frank and Marijune Wissmann’s wedding picture